Exploring leadership, virtue, and inner cultivation

In our April discussion, we explored the nature of effective leadership by examining the dynamics between what are often called “hard power” and “soft power.” While these terms initially suggest opposing strategies—force versus empathy, coercion versus influence—we moved beyond this binary. What emerged was a deeper insight: that truly effective leadership is rooted not in choosing one mode over another, but in discerning the most appropriate response to each situation, guided by internal principles like wisdom, virtue, and conscience.

Hard power is often defined as leadership through command, enforcement, or fear—often effective in achieving immediate compliance, but with risks of alienation or resentment. Soft power, on the other hand, often manifests through moral authority, empathy, culture, and relationship-building. Though slower in effect, it can foster deeper, more lasting influence. Rather than framing these as opposing categories or mutually exclusive approaches, we reframed the conversation around the idea that a wise leader doesn’t categorize their actions at all, but responds to the needs of the moment with discernment, guided by principle.

We proposed wisdom and virtue as central guiding qualities for such leadership. Wisdom entails the ability to discern what is appropriate in a given context and to act with clarity. Virtue, traced from the Latin virtus, includes strength, honor, and moral character—and is not simply about achieving outcomes, but about the inner quality of the action itself. Quoting Confucius—“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star…”—we emphasized that virtue can quietly guide others without needing force. Our Grand Elder Han was cited as a living example of this principle, serving as a moral compass through his personal example rather than directive authority.

This framework finds resonance across several traditions: the Buddhist Middle Way, Aristotle’s “golden mean,” and Confucianism’s Doctrine of the Mean (中庸). In each, virtue is not about passively splitting the difference between extremes, but about actively discerning and enacting what is most fitting for the situation—what is most appropriate, balanced, and true. At times, this may call for firmness; at others, for gentleness. What matters is not the outward form of the action, but the discernment, sincerity, and moral clarity from which it arises.

We explored this idea through examples of historical figures like Jesus, Gandhi, and Socrates—each of whom displayed great strength, not through domination, but through unwavering will and moral conviction. Their actions cannot be neatly categorized as hard or soft; they were simply right for their moment, arising from deep inner wisdom.

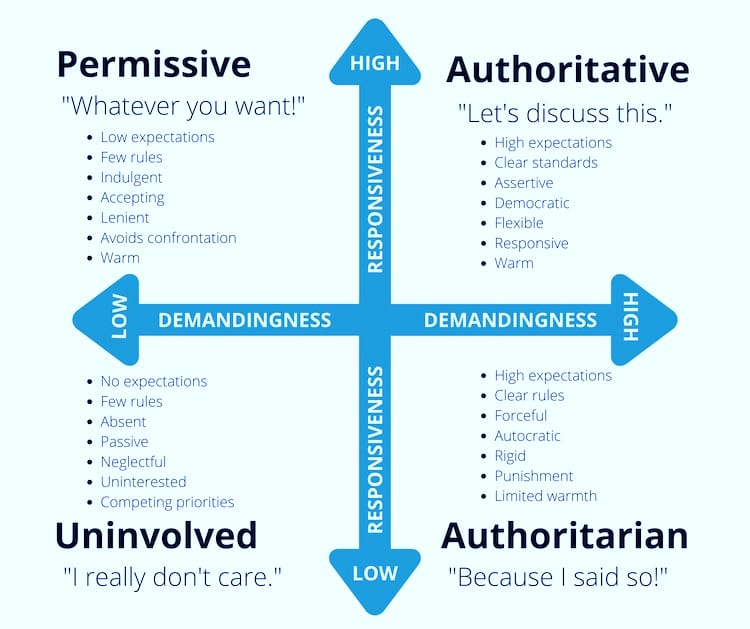

We also discussed a helpful framework borrowed from parenting psychology: the warmth-demand matrix. The most effective leaders, like the most effective parents or teachers, combine high warmth with high expectations. This “authoritative” approach models a kind of leadership that is both compassionate and principled, setting clear standards while fostering trust.

Trust became another key theme in our discussion. We recognized how fragile trust can be—and how vital it remains to the foundation of any true leadership. Trust, built through consistency and integrity, forms the invisible scaffolding for both authority and collaboration. We drew parallels to societal trust in institutions like the U.S. dollar, or legal concepts like the presumption of innocence—highlighting that trust and respect must underlie both soft and hard expressions of leadership.

From here, our focus turned inward. We agreed that leadership begins with managing oneself. Self-discipline—the ability to act according to one’s conscience even when no one is watching—is a hallmark of true integrity. A mature conscience provides the internal compass that, when widely cultivated across individuals, reduces the need for external enforcement. As one participant noted, if everyone lived according to their divine innate conscience, there might be no need for laws at all.

This led us to reflect on the well-known teaching: “Be strict with yourself and lenient with others.” We emphasized that this leniency does not mean permissiveness, but rather compassion coupled with clear guidance. True leadership, then, arises not from controlling others, but from the quality of one’s own character and actions.

Throughout the discussion, we drew from historical anecdotes, philosophical traditions, and personal observations to reinforce this central point: that effective leadership—whether of a nation, a workplace, a classroom, or oneself—comes not from wielding power, but from aligning one’s actions with wisdom and virtue. This alignment allows us to meet each situation with the response it truly calls for, without needing to label it as “hard” or “soft.” In this way, we move beyond the dichotomy altogether, and toward a form of leadership rooted in clarity, courage, and moral strength.